Insights

The fallacy of concentration

The dominance of large tech firms in market-cap-weighted indices has sparked recent concern about concentration risk, but historical data and empirical analysis suggest these fears may be unfounded.

October 2025

A review of nearly 90 years of market performance shows that reducing exposure based on concentration offers no timing advantage and actually worsened returns and risk. Sector-level concentration also fails to distinguish between high and low risk or strong and weak performance. Moreover, large companies tend to be safer due to their more diversified operational footprint and the increased investor and regulatory scrutiny they receive. Ultimately, the presence of concentrated capitalization weights has not proven to be a reliable indicator of bubbles or future market downturns.

Key highlights

In a market-capitalization weighted index, the largest stocks have the greatest influence on returns. Today, a handful of big tech firms dominate. Are such focused weights imprudent, or are they justified?

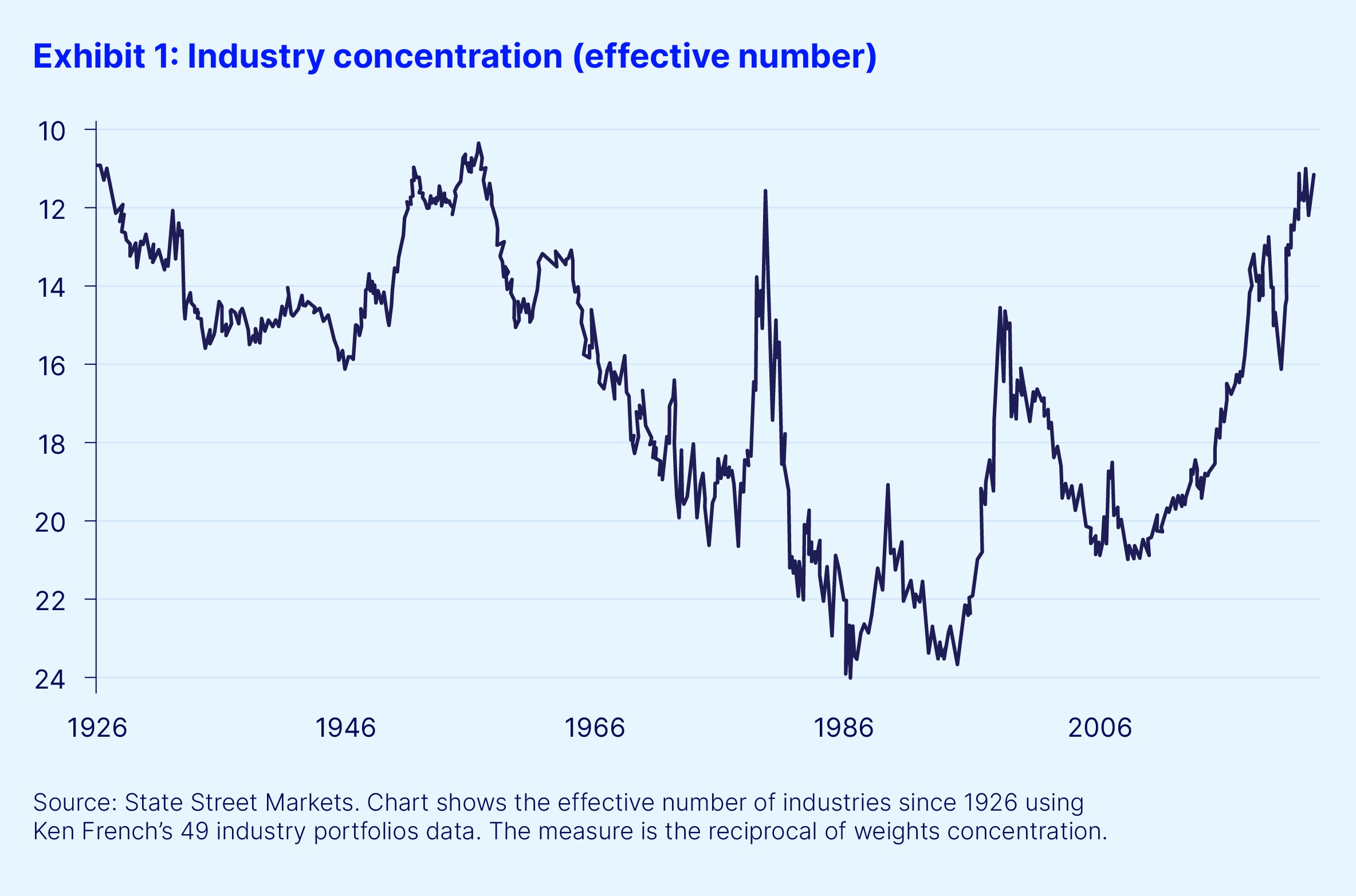

One has to look back almost 50 years to match today’s concentration (see Exhibit 1). The real question, though, is whether high concentration signals bad outcomes ahead. History does not show any such pattern.

In our paper on this topic we consider multiple angles. First, is it a good idea to scale back exposure to US stocks as the market index becomes more concentrated? We implemented this rule based on industry concentration dating back to 1936 and found that reducing exposure proportionally to concentration added no timing benefit. In fact, it generated worse returns and higher risk than a buy-and-hold position with the same average exposure to the index.

Second, we note that the level of concentration in US top-level sector indices varies dramatically across industries and across time. Does a sector’s concentration tell us anything about its return, volatility, downside volatility or maximum drawdown in the following year? A battery of predictive regressions reveals no meaningful relationships over the past 26 years. Avoiding concentration has not paid.

Third, we show that large companies are not equivalent to small companies. Large companies are safer. Consider, for example, that over the past 26 years the largest quintile of S&P 500 companies (eight stocks on average) totaled the same market cap as the smallest quintile (328 stocks on average), but the portfolio of eight had slightly lower volatility, less negative skewness and lower kurtosis of monthly returns. Intuitively, large companies are intrinsically more diversified and safer than small companies due to their client base, product breadth, geographical spread, and heightened scrutiny from investors and regulators. Concentration is a natural consequence of growth and the overall highly efficient allocation of capital. Bubbles do occur, but identifying and timing them is challenging, and weight concentration by itself has not offered a useful gauge for risk or return.