Insights

February 2025

Five forces reshaping the global economy: Insights for investors and policymakers

After a series of profound shocks – from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) to the COVID-19 pandemic and intensifying geopolitical tensions – the global economy faces a complex set of structural shifts that challenge traditional growth models and conventional policy tools.

Ramu Thiagarajan

Head of Thought Leadership,

State Street

Eric Garulay

Global Head of Content Strategy, State Street

Hanbin Im

Global Macro Researcher,

State Street

Summary

These interconnected forces – deglobalization, decarbonization, demographic change, soaring debt levels and rapid digitalization – are reshaping the trajectory of global growth and inflation dynamics, redefining investment strategies and testing economic resilience.

Recent crises have exposed the vulnerabilities of globally fragmented supply chains. In response, many economies are prioritizing greater resilience by localizing production. Yet, reshoring often raises costs, amplifying inflationary pressures. Emerging markets – heavily reliant on foreign capital and technology – face additional hurdles as their access to these resources erodes, further complicating their path to sustainable growth.

Decarbonization requires significant investments in renewable infrastructure and green technologies, increasing near-term costs and contributing to inflationary pressures. Cleaner energy and more stable supply lines could emerge over time, but this transition remains particularly challenging for developing countries due to their higher borrowing costs and limited capital availability.

Demographic shifts further complicate matters. Aging populations in advanced economies are driving up healthcare and pension costs while shrinking the labor pool, contributing to slower growth and wage inflation. In contrast, emerging economies with youthful populations have the potential to reap a “demographic dividend” if they successfully educate and employ their growing workforces. Overlaying these challenges is the mounting strain of historically high debt levels. Years of low interest rates and crisis-driven stimulus have expanded public borrowing, which reduced fiscal flexibility while debt servicing costs grew alongside rising interest rates.

Meanwhile, digitalization offers a counterbalance. Advanced tools such as artificial intelligence (AI) and data analytics are transforming productivity and innovation, enabling greater economic efficiency and helping offset inflationary pressures. However, the benefits of digitalization often require upfront investment and careful integration, underscoring the need for strategic foresight and long-term planning.

Understanding the complex interplay of these interdependent structural forces, and how they influence the broader economy, is crucial for institutional investors and policymakers.

This article examines these five transformational trends and their combined impact on growth, inflation, and monetary and fiscal policy, offering insights on charting a resilient path forward.

Contents

- Deglobalization: Reshaping trade, capital flows and economic stability

- Decarbonization: Transitioning to a low-carbon economy

- Demographics: Aging populations and youthful markets

- Debt: The mounting challenge to economic growth and fiscal flexibility

- Digitalization: The engine of innovation and productivity

- The interplay between the structural forces reshaping growth and inflation

- Leveraging data and emerging technologies to navigate global economic shifts

- Charting a resilient path forward

1. Deglobalization: Reshaping trade, capital flows and economic stability

From global supply chains to regionalized models

Deglobalization marks a structural shift from globally interconnected supply chains to regionalized production, driven by geopolitical tensions, protectionist policies and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, which have exposed the vulnerabilities in over-reliance on international supply networks. As a result, countries are increasingly turning to regional trade blocs and localized production hubs, moving away from the efficiency gains traditionally offered by globalization.1

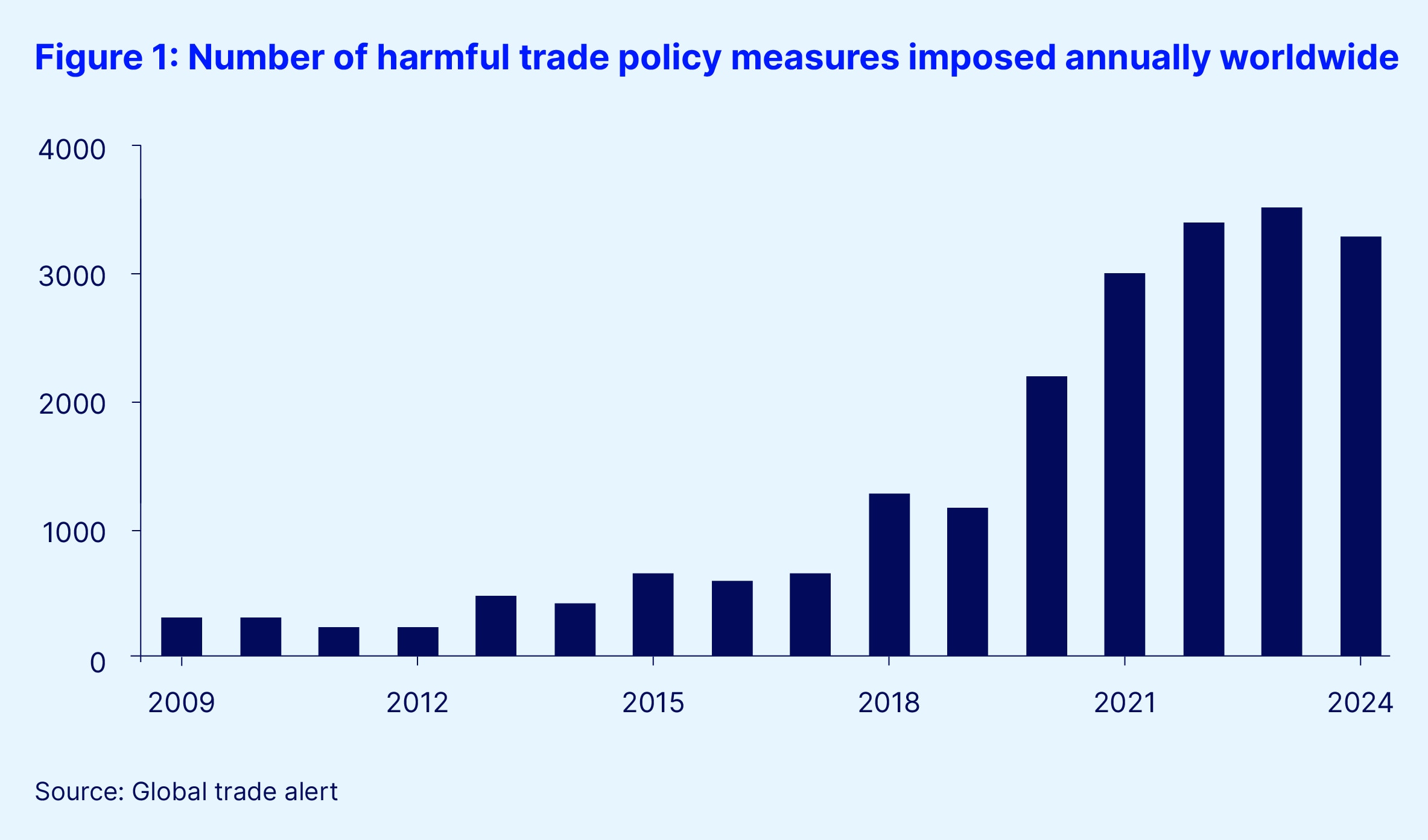

However, this shift raised costs and reduced productivity, especially in key sectors like manufacturing and pharmaceuticals.2 As trade barriers rise amid growing geopolitical friction, the rules-based “international order” is fracturing. Trade sanctions now occur four times more often than in the 1990s, while subsidies promoting domestic industries have surged globally.3 Since the onset of COVID-19, the number of harmful trade policy measures imposed annually has nearly tripled, rising from 1,174 in 2019 to 3,261 in 2024. This sharp escalation underscores the accelerating shift to protectionism and the fragmentation of global trade systems4 (see Figure 1).

Recent data underscores the economic impact of regionalization. A study of 163 economies revealed that since 2020, deglobalization has raised consumer price index (CPI) inflation by an average of 1.75 percent and core inflation by 1.69 percent, disproportionately impacting countries deeply integrated into global value chains.5 These inflationary pressures highlight the trade-offs of reduced global interdependence.

Financial fragmentation and capital flows

Deglobalization is also fragmenting financial systems, which reduces cross-border capital flows, hinders capital accumulation, weakens international risk-sharing and increases macro-financial volatility. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) finds that increased geopolitical distance between economies correlates with a 15 percent decline in cross-border portfolio and bank allocations, limiting access to foreign capital – especially for regions heavily dependent on international financing.6 Some countries, like those in Southeast Asia, have fortified domestic capital markets and increased foreign-exchange reserves to buffer themselves against global financial volatility.7 This shift toward self-reliance is reshaping global financial systems, reducing vulnerability to external shocks while limiting economic interdependence.8

Implications for economic growth and productivity

Deglobalization presents significant challenges to global economic growth and productivity, particularly in emerging markets. By limiting access to global markets and innovation, deglobalization raises production costs, restricts productivity and amplifies macroeconomic volatility.

The IMF projects that deglobalization could result in gross domestic product (GDP) losses ranging from 0.2 percent to as much as 7 percent in severe cases, with additional technology decoupling raising losses further to 8-12 percent for affected nations.9 This underscores the potential inflationary and productivity challenges of a fragmented economy. Emerging markets face heightened risks from deglobalization due to their dependence on foreign investment, technology transfer and integrated supply chains. Reduced access to international capital would stunt growth, particularly in economies that rely on global networks to support development.10 Without international collaboration, these markets may struggle to achieve growth rates necessary to reduce poverty and economic disparities.

Rising inflationary pressures due to regionalization

Regionalized supply chains drive cost-push inflation by reducing the comparative advantages of global networks. Sectors like manufacturing, electronics and pharmaceuticals are particularly impacted by rising costs due to tariffs and supply chain restructuring, increasing consumer prices and inflationary pressures.

Additionally, deglobalization disrupts supply chains, leading to cost-push inflation, especially in sectors like manufacturing and electronics. For instance, United States transportation costs for Chinese machinery surged from 5 percent to 46 percent of production value between 2016 and 2021, exacerbating inflation through tariffs and protectionist policies.11 Additionally, these increased costs are often passed onto consumers, contributing to inflationary pressures in advanced economies.12 This shift toward “friend-shoring” adds redundancy but also costs to supply chains, likely resulting in structural inflation due to higher production costs and potentially less efficient allocation of resources.13 Governments are also channeling significant resources into building localized production capabilities, which can intensify inflationary pressures.

These dynamics result in structural inflation as economies grapple with higher production costs, diminished economies of scale and less efficient allocation of resources.

Policy implications

To offset some of the inflationary and growth constraints of deglobalization while building a more sustainable and resilient global framework, policymakers may consider:

- Promoting regional trade agreements to maintain connectivity and reduce dependency on single trade partners. However, geopolitical considerations and national security concerns may limit the feasibility of certain agreements.

- Strengthening domestic supply chains through technology adoption, automation and workforce development, though resource constraints and competing fiscal priorities may slow progress in some sectors.

- Encouraging public-private partnerships to fund critical infrastructure projects, particularly in industries facing high inflationary pressures. However, variations in political will, budgetary limitations, and regulatory challenges may hinder execution.

- Incentivizing diversification of suppliers to reduce risks while maintaining cost efficiency.

- Fostering greater global financial cooperation to address capital flow fragmentation and ensure liquidity during crises. However, differing monetary policy objectives and fiscal constraints across countries may create coordination challenges.

While these policy measures can help mitigate the effects of deglobalization, governments must balance them with other domestic priorities, political constraints, and economic realities that may lead to trade-offs between long-term resilience and short-term stability.

2. Decarbonization: Transitioning to a low-carbon economy

The global shift toward decarbonization is reshaping economic priorities and driving significant investments in clean energy and infrastructure. Achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 will require an estimated US$275 trillion in investments, or roughly US$9.2 trillion per year.14 Current investment flows, however, amount to only US$1.3 trillion per year, leaving a substantial funding gap. Emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) are particularly vulnerable, as they face steep capital costs and limited access to green financing.15 These nations require an additional US$600 billion annually by 2030 to fund renewable energy projects.16 Greater foreign direct investment (FDI), concessional financing and supportive policies will be critical to bridge this divide.17

Economic impact: Short-term costs versus long-term gains

Decarbonization will initially create “greenflation,” as the demand for renewable infrastructure and critical raw materials like lithium and cobalt outpaces supply, thereby driving up input costs. These inflationary effects may be further exacerbated by “fossilflation,” resulting from constrained fossil fuel supplies. Investments in renewable infrastructure and green technologies may temporarily slow GDP growth by 0.15-0.25 percentage points annually and raise inflation by 0.1-0.4 percentage points.18

Despite these near-term challenges, global renewable capacity is forecasted to overtake fossil fuels by 2028, primarily led by China, the European Union (EU) and the US.19 The upfront costs associated with decarbonization are expected to be offset over time. As green industries expand, decarbonization is projected to generate up to US$2 trillion in annual savings by 2030, fostering more stable energy costs and long-term sustainable growth.20

Growth implications of decarbonization

The transition to a low-carbon economy presents both immediate challenges and future growth opportunities, with key implications for economic stability and investment potential:

- Short-term challenges from transitioning away from fossil fuels, with transition costs especially high for fossil-fuel dependent industries and exporting countries.

- Significant investment opportunities across the entire carbon neutrality value chain, encompassing infrastructure, equipment and green technologies.

- Long-term economic stability through a more diversified energy base, while transition investments drive innovation and productivity growth.

Inflationary implications of decarbonization

Carbon pricing and renewable adoption are expected to raise near-term costs significantly. For instance, a US$75-per-ton carbon tax could more than double coal prices, and increase natural gas by 60 percent, electricity by 25 percent and gasoline by 19 percent.21 These increases are expected to ripple through the broader economy, raising costs for goods and services dependent on fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, the demand for essential raw materials is projected to rise sevenfold by 2030, adding pressure on supply chains. However, technological advancements may mitigate these impacts over time.22

In sum, this shift to renewables and carbon pricing introduces near-term inflationary pressures, driven by the rising cost of fossil fuels and increased demand for raw materials essential to green technology:

- Inflationary pressure during this transition period due to “climateflation,” “fossilflation” and “greenflation” as the economy adapts to new energy and environmental standards.

- Long-term inflation stabilization resulting from the adoption of more efficient, cost-effective renewable energy sources and more resiliency against price volatility linked to fossil fuels.

Policy implications

More capital is required to achieve 2030 and 2050 climate goals. While green bonds and sustainable loans are growing, they are not yet at scale to meet these challenges alone. Patient capital and supportive policies can lower investment risks and help improve the flow of capital to green investments and green technology.

Further, policymakers must be prepared for sustained greenflation23 and may consider implementing measures, such as tax credits, carbon pricing and regulatory incentives, to attract private capital. However, the pace and extent of decarbonization policies will depend on broader fiscal agendas, energy security concerns, and the willingness of stakeholders — including businesses and consumers — to absorb potential short-term costs. Additionally, achieving global climate goals requires multilateral cooperation, which can be challenging given diverse economic structures and policy priorities across nations.

While these measures can help drive a greener economy, policymakers must carefully assess potential trade-offs, including the risk of economic dislocation, transitional costs for businesses, and the impact on energy affordability for households.

For many EMDEs, achieving decarbonization goals will depend on a combination of concessional finance, blended finance models and global policy coordination to reduce capital costs and attract private investment, balancing fiscal stability with environmental progress.24

Clear, consistent policies also provide the private sector stability for long-term planning.

3. Demographics: Aging populations and youthful markets

Divergent demographic trends

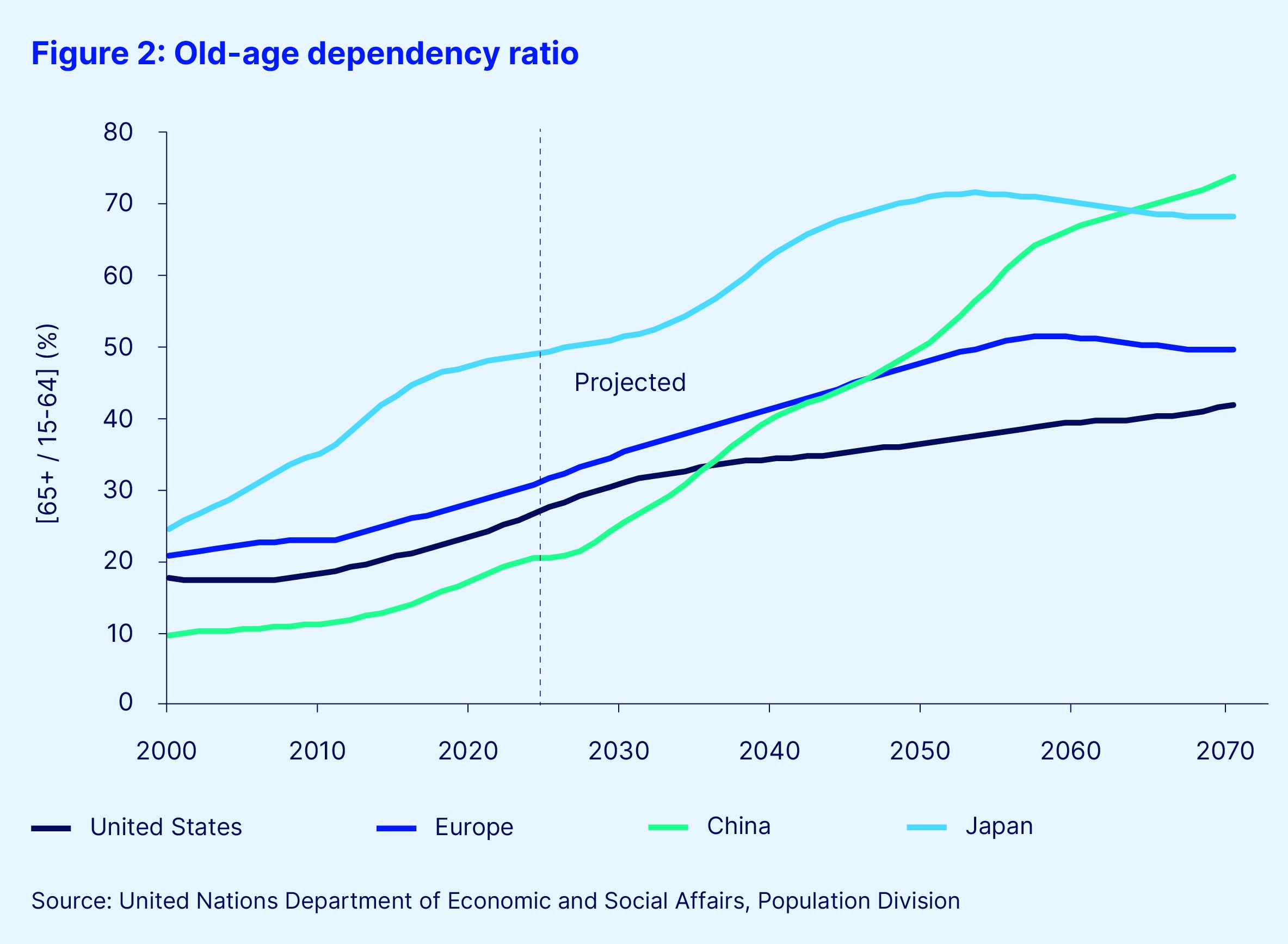

Demographic shifts are creating two starkly contrasting economic realities: aging populations in advanced economies and young populations in emerging markets. Advanced economies like Japan and parts of Europe face lower GDP growth and rising social expenditures as their dependency ratios – the proportion of non-working to working-age populations – climbs. For example, Japan’s dependency ratio now exceeds 50 percent, adding fiscal pressures and limiting growth potential.25 By 2050, the old-age dependency ratio in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries is projected to increase substantially, intensifying fiscal pressures on pensions and healthcare, which will further constrain growth.26 Additionally, aging populations contribute to cost-push inflation as labor becomes scarcer and wage demands increase.27

In contrast, emerging markets with younger populations have the potential to enjoy a “demographic dividend,” where higher productivity and lower dependency ratios support economic growth. Economies which have heavily invested in education are well positioned to capitalize on this demographic bonus, while regions with educational gaps may struggle to harness the same benefits.28 Emerging markets are expected to experience per-capita income growth of up to 3.8 percent annually through 2050, provided they can leverage this “demographic dividend” effectively.29

Youthful markets are also better positioned to adapt to the digital economy. Nigeria and India, for example, where median ages are among the lowest globally, could significantly benefit from digital industries like e-commerce and fintech. However, if consumption growth outpaces supply, demand-driven inflation in these economies could follow.30

Declining fertility rates and their impact

Global fertility rates dropped from 2.7 births per woman in 2000 to 2.3 in 2023, falling below the replacement level.31 In the US, the fertility rate hit a historic low of 1.62.32 China faces an even steeper decline, with a fertility rate as low as 1.1 nationally,33 and only 0.6 in urban areas like Shanghai, leading to a shrinking workforce and rising fiscal burdens.34

Projections indicate that, on average, the contraction of the working-age share of the population in developed economies could reduce per capita income growth by 0.54 percentage points.35 However, improvements in older adults’ functional capacity could reduce this impact by nearly half to 0.26 percentage points.36 By 2050, aging populations could reduce annual GDP growth by 0.4 to 0.8 percentage points in advanced economies.37

Economic growth implications of demographics

Aging populations in advanced economies may create labor shortages which stifle economic growth and exacerbate inflationary pressures. With fewer working-age individuals supporting a growing number of retirees, social spending demands rise, straining government budgets.38 For example, in China, by 2050, the over-60 population is projected to increase from 21 percent to 38 percent, illustrating the demographic pressure on resources and long-term growth.39

While shrinking working-age shares generally slow growth, improvements in functional capacity among older adults could offset up to half of this projected growth slowdown by enabling extended workforce participation, thus alleviating some “demographic drag.”40

In the Euro area, the old-age dependency ratio is projected to rise significantly, reaching more than 51 percent by 2070 according to the United Nations41 (see Figure 2). This increase will add pressure on pension systems, reducing the worker-to-retiree ratio from three-to-one to nearly two-to-one, intensifying fiscal burdens.42

Wealthy countries may need to allocate 21 percent of GDP to support their aging populations by 2050, up from 16 percent in 2015, mostly for healthcare and social services.43 While advancements in technology could theoretically lower costs, recent trends suggest they may, in fact, drive expenses higher.

Investments in health, education and flexible retirement policies are essential for maximizing the economic benefits of increased functional capacity and workforce participation. Without these supportive measures, the economic gains from improved longevity and capacity may not be fully realized.44

Projections indicate that, on average, public pension expenditures in OECD countries will rise from 8.9 percent of GDP in 2020-2023 to 10.2 percent by 2050, largely driven by demographic changes. In the EU, this increase is even steeper, with spending expected to reach 11.3 percent of GDP by 2050.45

As demographic trends diverge between aging advanced economies and younger emerging markets, the growth implications vary widely, impacting labor availability, productivity and fiscal sustainability:

- Growth constraints in aging economies stem from reduced labor force participation, slower productivity growth and higher social spending demands. Addressing these challenges requires innovation, automation and immigration reforms.

- Potential growth in younger economies depends on policies supporting education, job creation and productivity to position them for sustainable growth in global markets.

Inflationary and fiscal pressures from demographics

Demographic shifts generate distinct inflationary pressures across economies:

- Cost-push inflationary pressures arise in aging economies driven by rising healthcare and pension costs, and labor shortages.

- Deflationary trends emerge from slower growth and lower interest rates, which encourage saving but depress spending. High dependency ratios in aging populations further amplify deflationary effects by promoting higher saving rates and reducing overall spending.46

- Demand-driven inflation in emerging markets stems from rapid consumption growth, particularly if working-age populations cannot keep pace with overall population growth and dependency ratios remain high.47

Policy implications

Long-term projections suggest that without policy interventions, potential GDP growth in aging economies will continue to decelerate. For example, in the Euro area, declines in the working-age population are unlikely to be fully offset by migration or increased labor participation rates.48

To mitigate the risks of demographic shifts:

- Policymakers may consider boosting labor force participation through flexible immigration policies and education reforms. However, political sensitivities around immigration and fiscal constraints on education investments may limit the scope of such policies.

- Migration and participation rate improvements are crucial but may not fully offset shrinking workforces in aging economies. Policymakers may need to weigh these measures against broader social, economic, and political considerations.

- Technological advancements can help further offset the impact of shrinking workforces on productivity via automation and robotics. In this case, proper policies may be put in place to ensure automation does not result in net job losses in the working-age population.

Conversely, policymakers in emerging economies have the opportunity to harness the demographic dividend by equipping young people with the skills required for a productive workforce. However, job creation efforts, particularly in high-productivity sectors, must be balanced with broader economic strategies and fiscal constraints that may limit large-scale workforce development programs.

Ultimately, while these policy measures provide potential solutions, governments will likely need to remain adaptable to evolving demographic trends, economic conditions, and political considerations that may necessitate adjustments in approach.

4. Debt: The mounting challenge to economic growth and fiscal flexibility

Background and recent developments

Global debt has soared to unprecedented levels due to successive economic crises, expansive fiscal policies and historically low interest rates. Following the 2008/2009 GFC, governments and corporations borrowed heavily, embedding high debt levels into the structure of advanced economies.49 This trend accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitated fiscal stimulus packages, such as the $5 trillion issued by the US to bolster economic demand. However, these measures raised long-term fiscal risks, with global public debt projected to exceed US$100 trillion and approach 100 percent of GDP by 2030, driven by the US and China.50

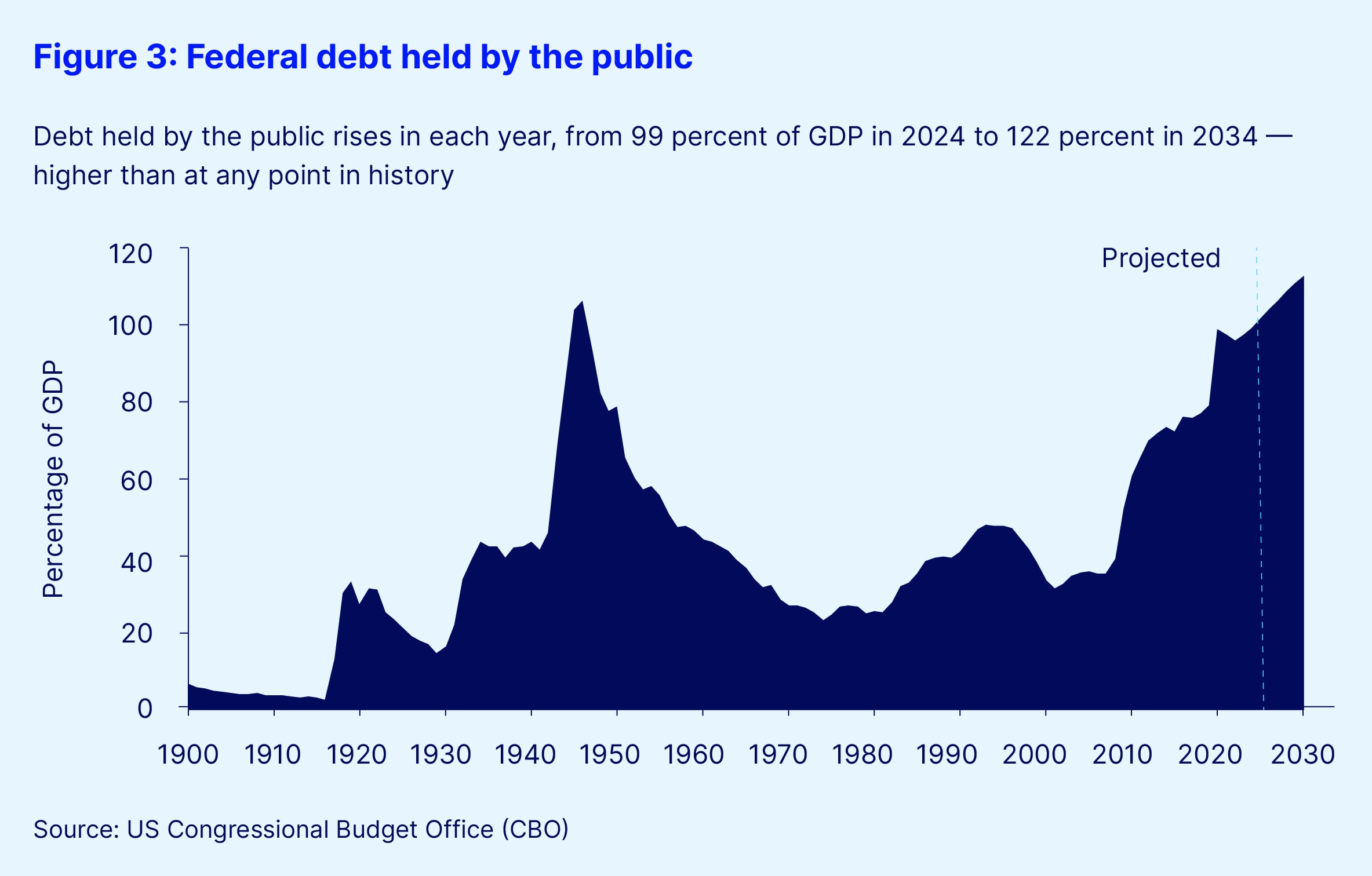

In the US, gross national debt has surpassed US$35 trillion,51 with publicly held debt projected to rise from 99 percent of GDP in 2024 to 122 percent in 203452 and 166 percent by 205453 (see Figure 3). Similarly, Japan’s gross debt-to-GDP ratio exceeded 260 percent in 2022, the highest globally.54 The US also faces surging interest payments, forecasted to climb from US$870 billion in 2024 to US$1.6 trillion by 2034, totaling US$12.4 trillion over the next decade.55 Net interest costs are expected to rise from 3.1 percent of GDP in 2024 to 6.3 percent in 2054,56 and interest payments could well rival other major federal expenditures such as defense and Social Security, highlighting the severity of the debt challenge.

Impact of rising debt servicing costs

Higher interest rates have significantly increased debt servicing burdens, constraining fiscal capacity. According to the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL), unsustainable fiscal policies can undermine central banks’ ability to manage inflation, heightening risks of capital outflows and defaults, particularly in emerging markets.57

Advanced economies, too, are seeing a growing share of government budgets allocated to net interest payments, limiting spending on public investments. For example, Japan’s fiscal year 2025 budget projected ¥28 trillion for debt servicing, about 24 percent of the total general account expenditure.58 In the US, interest payments are projected to reach US$728 billion in 2024, 16 percent of government revenues.59

High external debt reliance magnifies these challenges for emerging markets, with combined debt reaching US$105 trillion in 2024. Debt servicing demand often crowds out necessary development spending, with countries like Pakistan allocating nearly three times more to interest payments than to investments, curtailing growth and fiscal flexibility.60

Debt, inflation and fiscal stability

Rising interest rates exacerbate refinancing costs, adding upward pressure on inflation. In the US, each additional 0.1 percent rise in interest rates could cumulatively add US$324 billion to the federal deficit from 2025 to 2034, underscoring the scale of the vulnerabilities associated with servicing large debt loads.61

The US is projected to issue approximately US$2 trillion in Treasuries annually over the next decade to cover fiscal deficits – expected to total US$20 trillion over the 2025 to 2034 timeframe. To absorb this surge in supply, yields may need to rise by an additional 95 basis points, potentially driving up global borrowing costs and creating an even tighter environment for fiscal flexibility.62

The FTPL posits that inflation spikes when government debt exceeds what can realistically be repaid through future tax increases or spending cuts. As confidence in the government’s ability to repay wanes, inflation may surge as investors sell off debt holdings, preferring safer assets, which drives up borrowing costs and exacerbates the fiscal strain.63 High debt can thus become a self-reinforcing driver of inflation, pressuring governments toward austerity or aggressive monetary expansion. For policymakers, this structural debt burden further challenges sustainable growth by crowding out resources for investments critical to mitigating inflation and fostering productivity.64

Implications for inflation

Rising global debt levels carry critical implications for inflation, influencing both monetary policy flexibility and price stability:

- Risk of de-anchoring inflation expectations: If governments adopt looser monetary policies to ease debt servicing costs, inflation expectations may destabilize. This scenario heightens risks of volatility, particularly in emerging markets where fiscal constraints are more acute.

- FTPL: Persistent high public debt, without corresponding future surpluses, may lead economic agents to perceive an increase in real wealth, anticipating debt monetization. This expectation can boost consumption and prices, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

Implications for economic growth

High debt burdens constrain economic growth by limiting fiscal flexibility and diverting resources from productive investments, such as in infrastructure, education and research – key drivers of long-term economic growth.

Crowding out private investment may raise capital costs, especially problematic for firms with US$2.02 trillion in high-yield debt due from 2024-2029.65 Investor skepticism over debt sustainability increases yields and weakens growth prospects. Emerging markets, facing high debt and currency risks, struggle to finance green and digital transitions.66

Further, reduced labor force growth and productivity exacerbate long-term debt pressures by reducing taxable income and economic output. For instance, if labor force growth slows by just 0.1 percent, the cumulative deficit could increase by US$142 billion over the 2025-2034 period.67

In sum, high levels of global debt pose significant challenges to economic growth, affecting investments, fiscal flexibility and resilience against economic shocks, including:

- Crowding out of private investment through redirection of resources from productive uses, increasing borrowing costs for the private sector and reducing capital availability for private investments.

- Fiscal constraints on growth as rising debt servicing limits fiscal flexibility, reducing governments’ capacity to invest in sectors that are essential for driving long-term growth, such as infrastructure, education and health care.

- Increased vulnerability to external shocks due to limited fiscal space, which constrains governments’ ability to respond to economic crises or unexpected shocks.

Policy implications

Policymakers may consider implementing coordinated fiscal strategies to manage debt sustainably while fostering long-term economic growth. Key priorities include:

- Debt restructuring and enhanced transparency: These measures are critical for stabilizing investor confidence in advanced economies. However, political and market sensitivities may limit the extent to which debt restructuring can be pursued without unintended consequences, such as credit rating downgrades or capital flight.

- Concessional and blended financing: Emerging markets need access to such tools to ease debt burdens and fund growth initiatives. However, reliance on concessional financing may be constrained by donor priorities, geopolitical considerations, and broader fiscal constraints within lending institutions.

- Strategic investment in productivity: Debt-financed public investments can prioritize green infrastructure, digital innovation and human capital development to enhance resilience and promote long-term stability. Yet, political cycles and competing budgetary demands may lead to preference for short-term stimulus measures rather than long-term investment.

While sustainable debt management and fiscal policy alignment with monetary goals are crucial, governments must navigate complex trade-offs between economic growth, fiscal stability, and political feasibility. Additionally, external factors such as inflation, geopolitical risks, and global interest rate cycles may further constrain policymakers’ ability to implement optimal debt management strategies.

However, by focusing on sustainable debt management and aligning fiscal policies with monetary goals, policymakers may be better positioned to balance short-term stabilization with long-term economic resilience.

5. Digitalization: The engine of innovation and productivity

The role of digital transformation

Digitalization has become a key driver of economic growth by enhancing productivity through automation, advanced data analytics and innovative business models. By streamlining operations, improving resource allocation, minimizing errors and accelerating production, digital tools contribute to higher economic output.68 Additionally, sectors such as digital financial services and e-commerce also expand market access, particularly in underserved areas, driving economic inclusion and growth.69

Generative AI (GenAI) exemplifies the game-changing potential of digitalization, with its projected annual contribution of up to US$4.4 trillion to the global economy through labor productivity gains across industries.70 This advancement redefines digital infrastructure by enabling hyper-personalization, robust data analysis and synthesis, and streamlined operations, potentially accelerating economic growth while also influencing labor demand dynamics across sectors.

Digitalization’s growth outlook

Studies on digital transformation across OECD countries underscore the role of digital innovation in driving GDP growth, as digital solutions lower operational costs and boost productivity across a range of industries.71

Digitalization enhances value creation, enabling new economic models, particularly in data-intensive sectors such as finance and e-commerce, thereby expanding economic value and supporting GDP growth.72 Digitalization has also reduced barriers to entry and expanded market access – most notably in underserved regions. In Southeast Asia, for example, digital platforms have significantly advanced the tourism industry, enhancing service accessibility and real-time tracking capabilities, which has supported regional economic expansion.73

GenAI represents a transformative leap in digital capabilities, automating complex tasks across finance, manufacturing and logistics. This innovation strengthens forecasting capabilities, optimizes resource allocation and builds resilience in data-driven economic systems.

Digitalization is expected to continue to drive economic growth through:

- Achieving productivity gains and cost reductions via automation and streamlined operations.

- Spurring innovative business models, such as e-commerce and platform economies – digital ecosystems where businesses and consumers connect through online platforms to exchange goods, services and information – driving efficiency, scalability and economic growth.

Dual inflationary and deflationary effects of digitalization

Digitalization historically serves as a deflationary force by boosting productivity and reducing operational errors. During the pandemic, for instance, digitalization enabled rapid remote work adoption, which reduced productivity losses. Digitalization’s ongoing role as a productivity multiplier is expected to offset some inflationary pressures, especially as economies become more tech-integrated.74

Digitalization, particularly through AI, drives significant labor productivity growth, especially in high-AI-penetration sectors like professional services, IT and financial services, where productivity growth has been nearly five times that of less AI-exposed sectors.75 This effect can lead to broad deflationary pressures as AI reduces costs across industries.

However, while digitalization is typically deflationary, it introduces inflation in AI-specialist job markets, where roles requiring advanced skills command wage premiums of up to 25 percent.76 Additionally, investments in digital infrastructure, such as 5G networks and AI, often rely on debt financing, creating short-term inflationary pressures despite the potential for long-term productivity gains.77

In emerging markets, digitalization has a nonlinear impact on inflation: It can be initially deflationary up to a certain threshold, but may become inflationary as digital ecosystems mature and demand for highly skilled labor increases and advanced infrastructure costs grow.78 Investments in education and governance can help amplify the deflationary effects of digitalization, while surpassing certain digital development thresholds might diminish these benefits.79

Over time, digitalization is expected to moderate inflation by reducing operational costs and enabling better demand management. Technologies such as smart grids, AI and predictive analytics allow industries to minimize waste and optimize energy use.80 This capacity to streamline operations contributes to stable, predictable pricing, helping offset inflationary pressures elsewhere in the economy.

In sum, digitalization’s impact on inflation can be divided into two phases:

- Short-term inflationary pressure in certain sectors due to heightened demand for AI talent, tools and services, along with investments in digital infrastructure.

- Long-term disinflationary effects achieved through enhanced productivity, reduced operational inefficiencies and optimized supply chain management.

6. The interplay between the structural forces reshaping growth and inflation

The convergence of deglobalization, decarbonization, demographics, debt and digitalization introduces complex, nonlinear dynamics that shape global growth, inflation and market behavior. These structural forces do not act in isolation; rather, their combined effects can be disproportionately greater – or lesser – than the sum of their individual impacts, depending on the particular macro-economic context.

For instance, in aging economies like Japan, the combination of demographic pressures and rising debt burdens may amplify fiscal strain, reducing growth prospects while compounding inflationary risks. In contrast, in youthful economies such as India and Saudi Arabia, the synergies between digitization and decarbonization could drive significant growth, supported by demographic dividends. These dynamics underscore the importance of context, as the same combination of forces can produce markedly different outcomes across regions and economies.

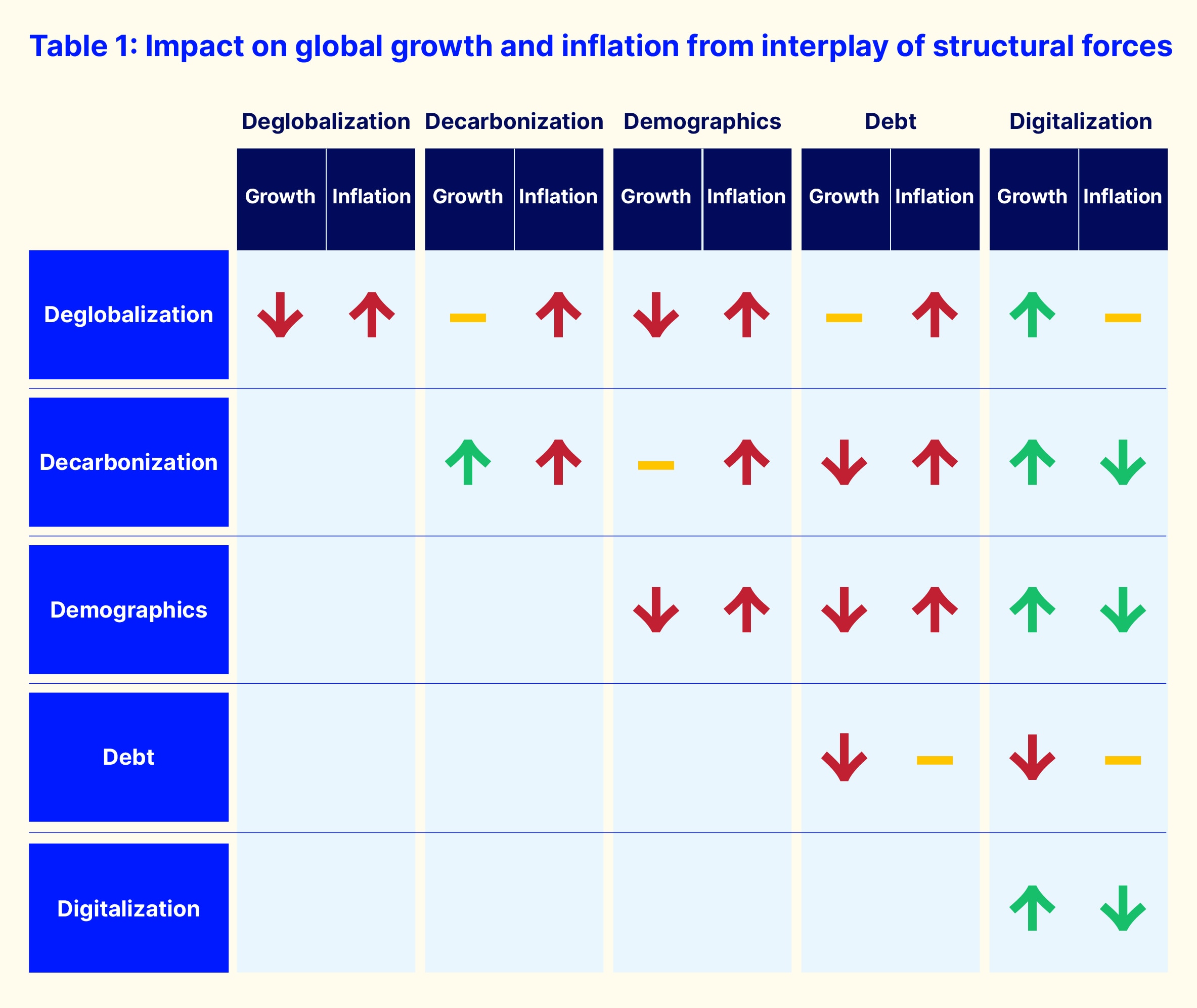

The following table illustrates the interplay between these structural forces, highlighting where they combine to amplify impacts on global growth and inflation.

This analysis focuses on the first-order effects of the two structural forces, acknowledging that the overall combined impacts – often non-linear – make predicting second- and third-order effects inherently complex. For example, both deglobalization and decarbonization constrain global sourcing, initially increasing costs as supply chains fragment. Over time, however, the localization and maturation of green supply chains can stabilize costs and foster long-term growth. Meanwhile, digitalization can offset some inefficiencies caused by supply chain fragmentation and reduce input costs for decarbonization through innovations such as smart grids, automation and data-driven tools. These advancements contribute to stabilizing inflation and boosting productivity. Ultimately, the interplay of these forces is shaped by macroeconomic conditions and the speed at which these structural shifts progress.

In summary, the interplay between these five forces suggests a structural shift that often leans toward higher costs and constrained growth potential. Deglobalization, aging populations and heavy debt loads tend to push up inflation and erode growth, as each hinders productivity and intensifies cost pressures. The effects are further magnified when these forces act in tandem. Decarbonization, while ultimately promising sustainable growth and lower energy costs over time, initially contributes to “greenflation” due to scarce inputs and high upfront investments. In contrast, digitalization consistently emerges as a mitigating force, improving efficiency, stabilizing supply chains and reducing input costs. When paired with digital tools and younger demographics, decarbonization and even partially deglobalized supply chains can transition toward healthier growth patterns with lower price pressures.

7. Leveraging data and emerging technologies to navigate global economic shifts

As the global economy faces the confluence of these five transformative forces, traditional methods of analysis and forecasting are becoming less effective. In this complex environment, stakeholders are increasingly turning to next-generation technologies to reframe how they interpret data, analyze trends and make decisions. Emerging technologies such as AI, GenAI, machine learning (ML), natural language processing (NLP) and cloud technology are no longer merely tools for enhancing efficiency – they have become critical dependencies for successfully navigating markets and economic shifts.

In today’s data-rich world, the sheer scope and scale of information presents both challenges and opportunities. GenAI and ML can now sift through vast quantities of data – both structured and unstructured – in real-time, uncovering patterns and insights that were once hidden in the noise. With emerging sources of data such as real-time sentiment analysis, alternative economic indicators, global supply chain metrics and geospatial data, these technologies enable a more sophisticated understanding of market trends and geopolitical risks. The future of intelligent investing and policymaking will hinge not just on the volume, range and quality of data, but also on how swiftly and accurately it is transformed into actionable insights.

8. Charting a resilient path forward

The global economy is undergoing unprecedented transformations driven by deglobalization, decarbonization, demographics, debt and digitalization. These forces are deeply interdependent, collectively reshaping growth trajectories, inflation dynamics and the distribution of economic opportunities.

The fragmentation of global trade, mounting debt burdens and the transition to a low-carbon economy are creating new risks and pressures, challenging governments and businesses to adapt. These trends threaten to exacerbate economic inequality, strain fiscal resources and destabilize global markets, underscoring the need for coordinated action. However, the path forward is neither straightforward nor uniform, as policymakers navigate competing domestic priorities, geopolitical realities, and fiscal constraints. The complexity of these challenges means that while ambitious policy frameworks can provide direction, their implementation will require careful sequencing, trade-offs, and adaptability to evolving economic conditions.

Whether the future leans toward persistent volatility or a new era of stability depends on how effectively leaders in the financial industry and beyond adapt to these structural shifts. How adeptly investors and policymakers leverage data and technology – not merely as ancillary support tools, but as strategic drivers – will determine whether these forces are met with informed action or reactive uncertainty.